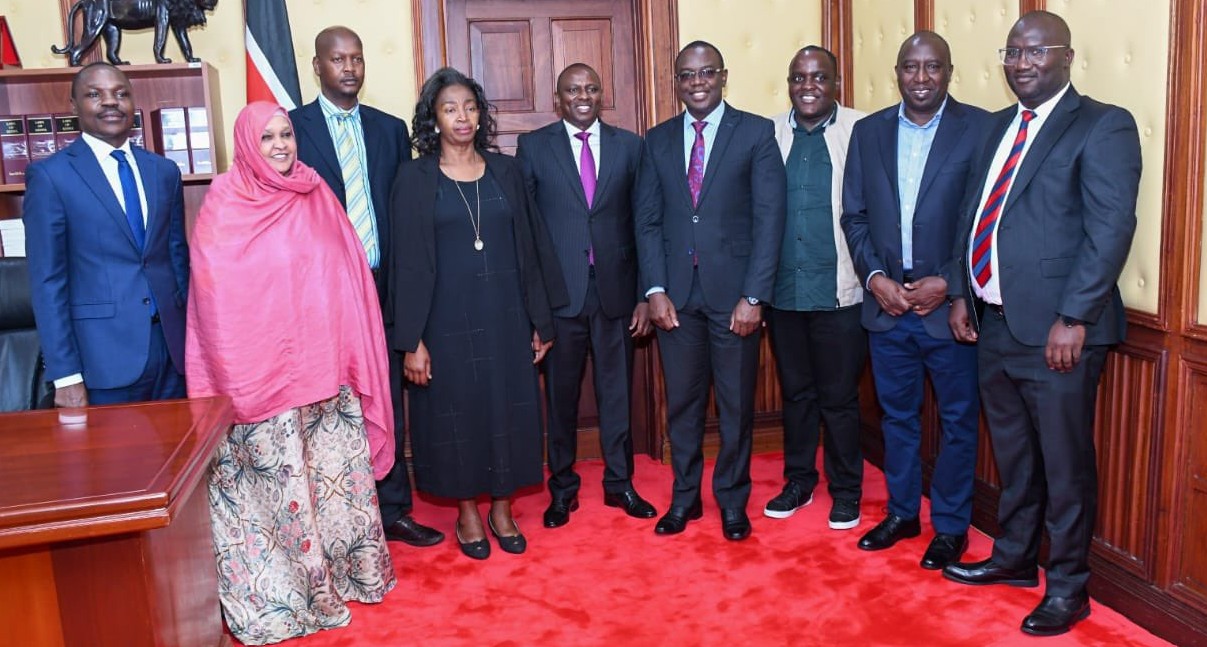

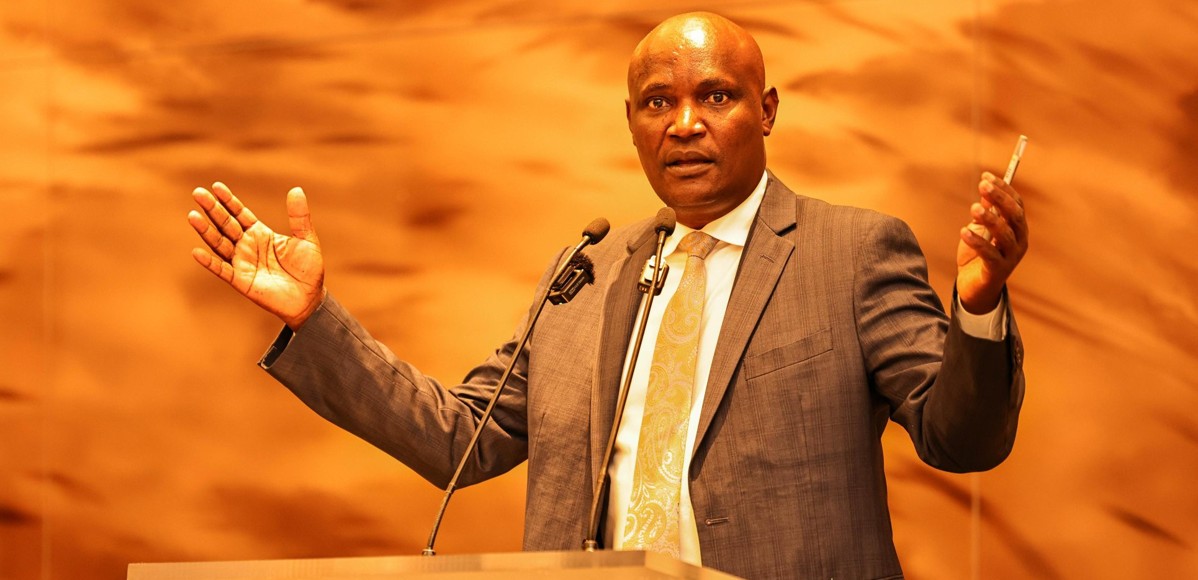

Kenya’s criminal gangs trace back to independence era, NCIC says

After independence, NCIC says the emergence and evolution of criminal gangs was largely influenced by politics, particularly the creation of the Kenya African National Union (KANU) youth wing. Initially formed to assist the police in fighting crime, promoting the party’s agenda, tree planting and soil conservation, it later evolved into an outfit for political mobilisation and enforcement.

The evolution of organised criminal gangs in Kenya follows a trajectory not far removed from the country’s independence story, a new report by the National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NCIC) has shown.

The Commission released a report on the Evolution of Organised Criminal Gangs in Kenya on Thursday. It traces the emergence of the first public gang activity to pre-independence Kenya, the period between the 1940s and 1960s, when young, disillusioned, jobless boys became the first gang members as they resorted to criminality to cope with socio-economic hardships.

More To Read

- Coastal counties face surge in online job scams, officials warn

- Cases of police misconduct rises despite overall drop in crime -Report

- IOM launches global campaign to support human trafficking survivors

- DPP calls for stronger inter-agency action on hate speech and incitement cases

- Court awards Sh5 million to Kenyan trafficked to Myanmar for online fraud

- Gachagua, governors, and MPs under probe by NCIC for inflammatory statements

During this period, the report says, Mau Mau fighters promised their supporters ithaka na wiathi- ‘land and freedom’.

They were, however, left disillusioned as only the colonial loyalists were rewarded with land, while the same rights were withheld from other supporters.

“The use of land to reward regime supporters and punish dissenters continued into the post-independence period, including during the reintroduction of multiparty elections in 1990,” the report explains.

After independence, NCIC says the emergence and evolution of criminal gangs was largely influenced by politics, particularly the creation of the Kenya African National Union (KANU) youth wing. Initially formed to assist the police in fighting crime, promoting the party’s agenda, tree planting and soil conservation, it later evolved into an outfit for political mobilisation and enforcement.

The wing became involved in organising commuters, participating in national celebrations, and occupying seats in District Development Committees (DDCs) and universities before eventually transforming into a militia and becoming a tool for political manipulation and violence, especially during elections.

NCIC recalls that prominent politicians utilised it to harass and disrupt opposition rallies, creating a climate of fear and intimidation. Their close relationship with the ruling party provided them with a degree of legitimacy and protection, allowing them to operate with relative impunity.

“Their actions contributed to a culture of impunity and normalised the use of violence for political gain in the coming years,” the report adds.

Ethnic-based militia gangs

Between the 1980s and the 2000s, more ethnic-based militia gangs were instigated by prominent politicians with state support and used to perpetrate violence against other communities.

The opposition, on the other hand, began forming its own gangs to protect itself and its political activities, especially during election campaigns.

“The result has been a growth of self-styled militias, vigilante groups, and organised criminal gangs in both urban and rural areas that have sprouted in almost every part of the country, posing an increasing challenge to the Kenyan police force,” the document states.

With a history of the ethnicisation of Kenyan politics, where political parties draw from core ethnic bases, NCIC says politicians have found youth militias and vigilantes to be important tools for enforcing party support and protecting individuals seen as ethnic leaders during elections.

Today, aided by technology and a growing population of educated but unemployed youth, Kenya is experiencing a rise in ‘gangsterism’ as a means of survival, economic advancement, or social recognition.

“The allure of quick money, a sense of belonging, and the perceived power associated with gang affiliation can be particularly appealing in the absence of legitimate pathways to success. Digital transformation has facilitated the emergence of online gangs, leveraging the anonymity and reach of the Internet to perpetrate crimes, spread disinformation, and incite violence. They exploit the speed and obscurity of the Internet to coordinate their activities, recruit new members, and disseminate their messages,” the report states.

The availability of social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, WhatsApp, and TikTok has become fertile ground for these groups, enabling them to mobilise quickly, spread propaganda, and incite violence with alarming efficiency.

NCIC notes that these platforms have been used during Kenya’s general elections to incite hatred and violence through ethnic hate speech, fake news, propaganda, and disinformation.

At the same time, increased demand for cheap labour, the growth of the sex industry, which often preys on poverty and conflict to exploit individuals for forced labour, and the relative ease with which people can be moved across porous borders have deepened the nexus between organised crime and human trafficking.

“The evolution of trafficking in Kenya is intertwined with the broader development of organised criminal groups. As gangs expand their operations and seek new revenue streams, they often diversify into trafficking, leveraging their existing networks and infrastructure for illicit purposes. This integration of trafficking into the portfolio of organised crime contributes to its growth and sophistication, making it more difficult to detect and combat," the report notes.

“Furthermore, the profits generated from trafficking can be used to finance other criminal activities, such as arms smuggling and drug trafficking, further strengthening criminal networks and their influence,” NCIC adds.

Today, while organised criminal groups capitalise on longstanding grievances, including land ownership disputes, limited job opportunities, unequal wealth distribution, and ethnic stereotypes, to fuel their violent activities, a clear pattern of heightened violence and criminality accompanies each electoral cycle.

Politicians often exploit this instability by incentivising participation in violence through cash rewards, land, and even the spoils of looting.

The report warns that, if left unchecked, the evolution of such networks can lead to state capture and the emergence of a criminalised state.

“As criminal networks gain power and influence, they may seek to infiltrate state institutions and manipulate policies to their advantage, leading to state capture. State capture can also occur behind the scenes, where lines between the state and organised crime become blurred and state institutions become complicit in criminal activities. In this case, policies are manipulated by private interests for their own benefit, undermining the public good,” NCIC says.

In Kenya, according to the Commission, the situation is even more severe, as state officials are directly engaging in criminal enterprises, using state resources for illicit purposes or protecting criminal organisations.

In 2012, a report by the National Crime Research Centre (NCRC) identified 46 criminal groups in Kenya, a number that had significantly increased by 2017 to 326, with 116 operating in 15 counties despite a 2016 government ban outlawing 90 such groups.

“This proliferation of organised criminal gangs, both in urban and rural areas, presents a clear and present danger to national stability and individual security,” the report warns.

Top Stories Today